(IAP ’12) Diana Jue G

Diana Jue traveled to India to implement Essmart. Essmart is an essential technology distributor with an in-store presence. Currently, essential technologies such as bicycle-powered machines, affordable solar lanterns, and smokeless cook stoves designed for the bottom of the pyramid are not well distributed. Essmart combines process innovations in product sourcing, distribution, marketing, and after-sales service to bring essential technologies to their intended end-user through rural retail stores. As part of our pilot phase in southern India, two rural shop owners sold all of our 17 demonstration products within one week

Eighth Blog – Feb 6, 2012: Wrap-Up and Reflections

I’ve made it back to Boston and am spending too much time on follow-up reports for Essmart’s gracious funders, including the MIT Public Service Center, Legatum Center at MIT, MIT International Development Initiative, and the MIT IDEAS Global Challenge. Thank you!

Here are some highlights from Essmart’s IAP, as written in some of our follow-up reports:

In January 2012, Essmart conducted 200 surveys with retail shop owners in southern India. We began operations with two shops near Pollachi, Tamil Nadu. As part of our pilot phase, they sold our 17 demonstration products within one week. We also continued establishing relationships with essential technology suppliers around India, networked with other social entrepreneurs at the Deshpande Development Dialogue in Hubli, and met with potential partners in Bangalore and Chennai.

Essmart was received positively by rural shop owners, as Tamil Nadu’s solar market is very good. We will soon begin the second phase of our pilot, which will include more product types, product brands, and product and customer record-keeping. Additionally, we are moving forward on partnerships with suppliers and collaborators in the upcoming months.

To conduct our surveys, Essmart enlisted four Masters students from NGM College in Pollachi, three students from SDM Institute of Technology in Ujire, and four SELCO Labs employees from Ujire (SELCO is a partnering social enterprise that develops new technologies for rural farmers). All together, Essmart employed or empowered 11 individuals through our survey efforts. Our surveys included a list of 12 technologies that Essmart is interested in distributing: solar lanterns, water filters, fuel-efficient cooking stoves, energy-efficient coolers, drip irrigation systems, pedal-powered generators, solar inverters, water transporters, mosquito bats, coconut tree climbers, coir ratt winding machines, and wheelbarrows. These surveys were given to 200 rural shopkeepers, most of who learned about the products through the surveys. Thus, these storeowners were also empowered by new knowledge of these technologies. We began working with two storeowners, who profited from selling our demonstration products. The 17 demonstration products (lanterns and water filters) that were sold in January probably went to 17 different households, affecting the lives of around 60 people. Thus, Essmart has employed or empowered over 270 individuals through its activities in southern India during January 2012. Seven individuals earned money from their activities with Essmart, either through surveying or through selling Essmart-distributed products.

From my time on the ground, something crucial that I saw was the importance of after sales service. It is all too easy to sell inexpensive products on the ground. The real problem comes when these products break down or require maintenance. Essmart does not want to flood the market with technologies without ensuring that end users benefit from them as intended. As part of our social mission, we must include after sales service. Additionally, we know that providing good service builds Essmart’s brand, and our brand is going to carry us in these rural markets. We have thus adjusted our business model to reflect how important we consider after sales service to be.

On a personal level, I feel all the more convicted to return to India after I finish my degree program in June. The problem that Essmart addresses – that is, the distribution of social impact technologies – is something that has bothered me since I was an undergraduate at MIT. To have the opportunity to address this problem is a dream come true. The journey will be difficult, but I look forward to learning a lot as Essmart continues its efforts throughout the spring semester and into the future.

Seventh Blog – Feb 1, 2012: Thinking about Rural Distribution from Bangalore, India

Rural distribution of social impact technologies requires cracking a number of tough nuts. What do Essmart and other companies attempting rural retail and distribution have to consider?

- Picking the right technologies. In terms of products, there is a lot of junk out there. For example, solar-powered products tends to have a bad reputation among rural populations because so many products break. The products need to be of high quality and appropriate for the population in terms of usage and price. Giving end users choice in the matter is also important. Kopernik is one organization that aggregates social impact technologies for NGOs, but its vetting process and customer feedback collection processes could be improved.

- Marketing. These technologies are not pull technologies, but they are push technologies. Push technologies, it seems, require intense, in-person marketing in the form of demonstrations and promotion by trusted community individuals. There are few marketing channels that reach rural populations, and there is no one brand that sells products across categories for rural consumers. Frontier Markets is really strong because of its on-the-ground presence through demonstration centers.

- Sales. This often involves sales agents or village level entrepreneurs who sell door-to-door (Sakhi Retail and Project Dharma). There might be a retail store that sales agents are associated with (Villgro Stores, Desta Global). It seems that sales agents are difficult to find, though. That’s why Essmart is using shop owners as sales agents – they already know how to sell. However, shop owners won’t push products. I’ve even been told that customers become suspicious if shop owners push a particular brand.

- Pricing and financing. The various companies I’ve seen in rural distribution haven’t really addressed the financing question. Most expect their end users to pay upfront in full, trust the middle man (e.g. the retail store owner) to take care of credit on their own informal basis, or provide credit themselves, which creates a huge cash flow issue. I think that price is one of the hugest obstacles to disseminating these technologies. CK Prahalad’s Fortune at the Bottom of the Pyramid might have raised a lot of false hopes, but one thing it did teach was that $1/day is much less expensive than $30/month for low-income customers. Thus, the appropriate pricing scheme would make waves. One company that I’ve seen addressing this problem with technology is Simpa Networks, which is trying to help finance the solar systems installed by SELCO through a scheme that imitates prepaid mobile phone recharge cards. Applying this type of thinking to buying consumer durable products could make a big difference.

- Moving the technologies. From what I’ve seen, companies involved with rural distribution to local kirana stores hire couriers or have their own vans, such as Drishtee and United Villages. I guess this gets the job done, but there might be a better way that has great reach with less overhead.

- After sales service. For consumer durables, after sales service is key – especially if the products are new and not branded with a big name. After sales service gains loyal customers and ensures that technologies don’t end up as trash by the roadside. Frontier Markets also takes care of this through the demonstration centers, which are also service centers. Additionally, it is important to really understand why products fail. Failure might be due to user error, or it might be due to mishandling, or it might be due to shoddy products. No manufacturers of social impact technologies do thorough problem analyses.

Right now, Essmart is piecing together this puzzle through a number of partners that are located in the US and in India. We want to make Essmart scalable so that it has impact in more than just one region, which is the case for many of the rural distributors/retailers out there. Is this possible, given the diversity of India’s rural population? I do think that there are aspects of this puzzle that can operate independently of local culture. There are solutions that have worked for the Bottom of the Pyramid, such as microfinance and mobile phones. These work because they address realized needs and present obviously favorable customer value propositions. But will social impact technologies automatically generate this kind of thinking?

Sixth Blog – Jan 27, 2012: Meeting SELCO Labs and Surveying around Ujire, Karnataka, India

After Pollachi, I took a train from Coimbatore to Mangalore and then took a bus from Mangalore to Ujire. Ujire is a small town of about 14,000 people. It is home to SDM Institute of Technology, where SELCO Labs has an office. SELCO is a well-known social enterprise that installs solar home lighting systems in the state of Karnataka. Anand Narayan, SELCO Labs’ Manager in Ujire, agreed to be one of Essmart’s project supervisors for IAP. We could not be more grateful for the opportunity to work with SELCO and to learn from their experiences in rural distribution.

In the end, we finished about 70 surveys with Ujire, utilizing the help of SELCO Labs employees and student interns. One of the SELCO employees, Sam, included a new technology into our catalogue survey: a wheelbarrow. Our surveys have yet to be processed, but they are sure to produce interesting results.

SELCO Labs at SDMIT in Ujire, Karnataka.

SELCO Labs Manager, Anand Narayan, educates youngsters on the basics of solar

Surveys begin in Ujire and neighboring towns.

Fifth Blog – Jan 24, 2012: Beginning Essmart’s Inventory Experiment in Pollachi, Southern Tamil Nadu, India

This was an exciting day for Essmart. The inventory experiment begins (although on a very limited scale)! In the morning, we met with our students to demonstrate the different products. Afterward, they gathered more products from Prashanth’s car and went off, two by two, to two different stores. In the stores, they demonstrated the products and hung up the Essmart banner.

Update: Our 17 items sold out from the two stores within one week! Store owners have been calling Prashanth and one of our student workers for more products. This is wonderful news for Essmart, and it confirms our idea about advertising through a paper catalogue and demonstration products in rural stores.

Fourth Blog – Jan 22, 2012: Survey Work in Pollachi, Southern Tamil Nadu, India

I and my Chennai-based teammate, Prashanth, road tripped down to Pollachi from Essmart to start survey work and Essmart’s inventory experiment. With the hard work of four Master’s students from Pollachi, we were able to roll out 130 surveys.

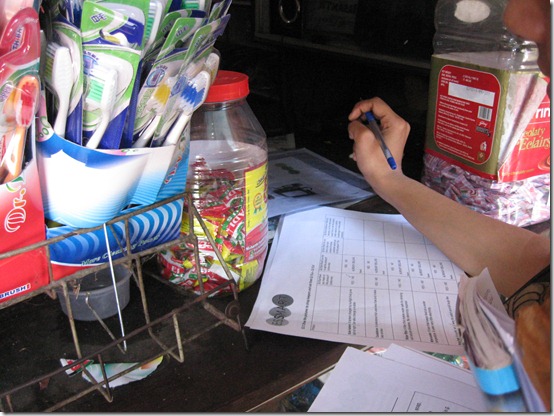

Essmart’s beautiful surveys, which include questions about the shops and about their interest in an array of products.

Our first meeting with the students. Prashanth gives them an overview of Essmart and the survey.After Prashanth’s introduction on our first full morning in Pollachi, the students split up in four different directions to begin surveying. The goal was to complete 15 for the day. I joined Eknath, who Prashanth said was the most eager to survey from the beginning. We traveled by what is becoming one of my favorite forms of transportation: motorbike. There’s nothing like whizzing past farmland on the back of a motorbike.

The first store we stopped by was a huge supermarket. Eknath, who is getting his Master’s in Social Work and has a lot of survey experience, was pretty professional in getting this information. The first survey went well, and the shop owner was interested in Essmart’s products (more on that soon). We surveyed on, skipping lunch to make sure we finished 15. With each shop, I stepped further back. It was faster for Eknath to handle the surveying alone, since he wouldn’t feel compelled to translate everything for me. I observed the interactions and gauged shop owners’ interest from afar, answering Eknath’s questions as they came up. I also took a lot of pictures:

The first round of survey results were interesting. We found that Tamil Nadu is a great market for solar – especially solar lanterns and solar inverters. Finding this out made me think, Wow, this can actually work. And, wow, we need to incorporate quickly. We finished about 60 surveys, thanks to Prashanth’s big thinking and incentives scheme.

After debriefing with the students, Prashanth and I got the technologies out of his car. We took stock. The inventory: Five each of d.light S250s, S10s, and S1s, five Envirofit G-3330 cooking stoves, one Envirofit LED lantern, one BOPEEI solar panel/mobile charger/lantern, and one Tata Swach. Not a lot, but at least it was something. Were we really going to begin selling these things? We would figure it out later.

Third Blog – Jan 16, 2012: Deshpande Development Dialogue in Hubli, Northern Karnataka, India

After Jaipur, I hopped a plane to Bangalore and then a plane to Hubli in Northern Karnataka. The Deshpande Foundation was hosting its annual Development Dialogue, a conference that brings together social entrepreneurs from all over India (although mostly in the south). This year’s theme was “Thriving in Ecosystem.” Hubli is the location of the Deshpande Foundation’s Sandbox, and this sandbox imagery is supposed to elicit children’s innovative and enthusiastic playtime. The Deshpande Foundation, which is led by Guraraj “Desh” Deshpande, hopes to bring out innovation and enthusiasm to solving social problems on the ground. In his introductory address, Desh talked about the process of globalization that provides opportunities for every nation if it is willing to compete, the global passport of high quality education, commitment, hard work, sincerity, and discipline, the necessity of respect for each other and true secularism (in the Indian sense of the word), and climate change.

Day 2 of Development Dialogue included a nifty keynote speech from Desh and a very forward breakout session discussion from Neelam Chhiber, co-founder of Industree and its related retail outlet, Mother Earth.

What stood out in Desh’s keynote, which ran extra long because the the panel immediately following his speech was missing a person (and, my, how Indians can talk like words are water), are 1) the concept of “compassionate capitalism,” 2) the necessity, again, of a good ecosystem for social entrepreneurs, and 3) innovation in India that is scalable and affordable. The Deshpande Foundation Sandbox is supposed to be a place where social entrepreneurs can “play” and “innovate.” Failures matter not; if something doesn’t work, you’re not supposed to become defensive. Rather, you continue playing. And social entrepreneurs must make a bottom line on inexpensive products that are designed to be scalable. These products, like a mobile phone, should be good at doing one thing really well. The NGO world lacks discipline, with organizations attempting to do too much.

I really enjoyed hearing from Neelam Chhiber, who spoke both in the panel discussion and in the breakout session that I attended. Neelam stressed a few things from her experience in the creative industry and supply chain management (her company essentially sources handicrafts from rural artisans and sells them as niche goods at tremendous margins). First was the necessity but difficulty of running a hybrid model. Industree is actually composed of two separate organizations. One is a for-profit private limited. The other is a nonprofit. The for-profit buys, sells, and makes a profit. The non-profit helps organize and train self help groups of artisan producers. Essmart is also considering a hybrid model to take advantage of different relationships and funding sources that just one legal entity cannot access. Neelam’s second point was the importance of having working capital for R&D, particularly in the design of new technology. She related new production technologies to the debate around “pure” handicrafts. She claimed that she was not in the handicrafts sector, but in the livelihood sector, so it did not matter what processes were used in making the products. The only thing that mattered was the producers’ livelihood. Lastly, Neelam stressed the importance of branding. Mother Earth substantially marks up the prices of its goods, and the goods are marketed to urban dwellers and international folks alike who care about doing some good through their purchases.

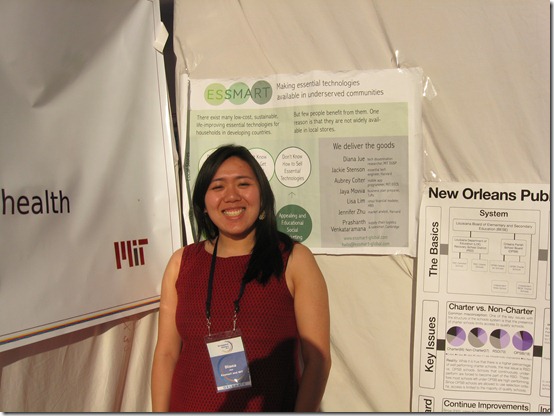

I spent the last few daylight hours standing in front of the Essmart poster that I carried all the way from MIT. It came with me to Los Angeles, Chennai, Jaipur, Bangalore, and to Hubli. Thus, its unveiling was less than spectacular because of the dents! But, oh well, at least it came through. I met a handful of people who were interested in what we’re attempting to do. For example, a few NGOs were also interested in distribution. As a team, Essmart needs to discuss the best way to enter into relationships with NGOs. I also talked with a few legal people, as well as an investor or two.

Second Blog – Jan 12, 2012: United Villages in Jaipur, India

I hired a car for the day and headed to the headquarters of United Villages, which is the main reason I came to Jaipur (no, it was not to look at pretty buildings). United Villages (UV) is a rural distributor of fast moving consumer goods. Its origins are at MIT, and it also has roots in Development Ventures (DV). Amir Hasson, MIT alum, spoke in class one day last fall. After he spoke, Jackie and I were like, “Whoa, they’re doing what we want to do.” Around Jaipur, UV has a network of stock transfer points and sales guys on motorbikes. Armed with smartphones that are equipped with UV’s web application, the sales guys visit between 25-40 stores a week to take orders. These are tiny stores, sometimes serving villages with 1,500 to 2,000 people. Deliveries are made weekly, with a minimum order of Rs 500 (about $10). The margins are small, but the volumes are getting larger. UV sells about 300 different types of products, from well known name brands to locally manufactured brands. They’re even begin to brand themselves by putting locally manufactured products under the UV brand.

UV wants to begin moving into consumer durables. For them, these durables mostly mean electronics. They’ve begun to include a solar inverter in their mobile catalog, along with a solar flashlight. Durables can be more difficult than consumer goods. Even though they’re higher value products, they require much more marketing (particularly if the product is new), and customers want after sales service. Thus, UV is mostly stock durables that come with a warranty and are produced by existing, trusted, branded companies. The company wants to begin moving into social impact products, too, but they need someone to take care of the on-the-ground marketing and education.

After my visit in the Jaipur offices, the CEO, Chintan Bakshi, arranged for my visit to the nearest field operations in Bassi. Bassi is about 40 km away from Jaipur, and I surprised my taxi driver with the idea of leaving the city. When we got to Bassi, I was met by the area sales manager. He and another UV staff member showed me various “counters” in Bassi. We visited the one cell phone counter, selected because he is the most entrepreneurial in the area. We visited multiple “general” counters that sell items like soap and shampoo, mostly by the sachet. Then, we visited one durables counter that sold products like televisions, refrigerators, satellite dishes, lights, heaters, etc. These are the types of stores I am most interested in, and it’s the type of store that UV is just begin to acquire as customers. Lastly, we drove a bit further and visited tiny, tiny stores that are also being serviced by UV.

I was impressed by UV’s reach. Serving small stores in tiny villages – where it is calm and peaceful, where there is no hustle and bustle – is pretty remarkable. It would be too easy to overlook these shops. After all, the larger village is just down the street, perhaps at 10 minute bike ride away. That is UV’s customer value proposition. Before, the shopkeeper would have to close up shop and travel to the larger village to buy his/her goods. The process could be an expensive hassle.

In the taxi, I had a phone call with Daniel Tomlinson from Frontier Markets (FM). FM also does what we want to do, except it uses the model demonstration centers with associated sales people. FM works around Jaipur, so there is already huge potential for collaboration between them and UV. Daniel basically said that Essmart should take a step back to truly understand rural markets before trying to do anything there. Since he had a good point, I took no offense to that. Also, he highlighted once again that villages across India are different. If Essmart wants to start in the south, we need to understand the culture. I suppose that another activity for us to do in Pollachi is to meet with some NGOs/MFIs/SHGs (nongovernmental organizations / microfinance institutions / self help groups) to answer some of these questions. Will talk with Prashanth about that.

Meeting or talking with other companies that are working in the space we want to inhabit is always helpful to Essmart. From their examples and experiences, we can more easily see which puzzle pieces are required to distribute essential technologies to rural customers. Definitely, key pieces are the marketing and the after sales service. These are areas that current companies are addressing. However, no one has really figured out the financing bit or how to cut down on the delivery costs. There is a lot of overhead in rural distribution, and cutting costs through innovation is key to making a business survive out there.

Please visit my personal website for more updates!

First Blog – Jan 7, 2012: And I’m Off to India!

Greetings from the happy skies! Finally, after months of preparation (finally culminating into a fantastically frenzied packing spree at the end), I am en route to Chennai, India (via Dubai, UAE) to work on Essmart, my Public Service IAP Fellowship project. Essmart is a social enterprise start-up working in India that my team began working on in the fall. Our mission is to get products that are designed for low-income communities into the hands of the people they were designed for. Here’s an introduction to Essmart from our latest executive summary:

Greetings from the happy skies! Finally, after months of preparation (finally culminating into a fantastically frenzied packing spree at the end), I am en route to Chennai, India (via Dubai, UAE) to work on Essmart, my Public Service IAP Fellowship project. Essmart is a social enterprise start-up working in India that my team began working on in the fall. Our mission is to get products that are designed for low-income communities into the hands of the people they were designed for. Here’s an introduction to Essmart from our latest executive summary:

“Many organizations designing bicycle-powered machines, solar cookers, and other life-improving technologies for developing countries lack effective distribution channels, and these technologies are not adopted by millions of intended users. This has happened to many winners of prominent business plan competitions: when the winning product-centered social venture begins, it quickly realizes that marketing, sales, and distribution pose the biggest challenges to achieving economic viability and scaled social impact. Why? First, technology-for-development initiatives concentrate their resources on product design, not dissemination. Second, distribution networks and advertising for the last mile are not well established. So, product-centered social enterprises cannot increase their revenues through sales, and few people benefit from social impact technologies.

The problem is technology dissemination, and Essmart offers a solution. While everyone else focuses on product design, Essmart delivers the goods.”

How does Essmart deliver the goods? By acting as a distributor of social impact products to rural retail stores. Ninety-seven percent of the $260 billion annual retail spending in India still takes place in these small, family-run shops that are often less than 50 square meters of space. These stores are a primary shopping stop for the 192 million Indian households not met by modern retail. And the nation itself has over 10 million of these local kirana shops that maintain tight relationships with hard-to-reach communities. We are assuming that one reason why social impact products do not widely reach their intended users is because they are unavailable at their shopping destinations. The products are unavailable because shop owners don’t know about the products, shop owners don’t know how to get the products, and shop owners don’t know how to market the products. Through our business model, Essmart is trying to address each of these problems for rural shop keepers.

In IAP 2012, my task is to see whether Essmart’s ideas about technology dissemination work. I will be traveling to a number of cities and villages that are mostly in southern India: Chennai, Jaipur, Bangalore, Hubli, Ujire, and Pollachi. In these places, I will be meeting with potential business partners, suppliers and customers (kirana shop keepers), doing community demonstrations of a handful of social impact products that are now available in India, learning more about the current situations of rural retail, and connecting with other entrepreneurs in India’s social sector. Essmart’s work will continue throughout the spring semester, too, in the form of a bootstrapped inventory experiment that will help us determine preferred technologies.

I am more than excited about my fourth trip to India. My last visit was in August, and I have been anticipating my return ever since. I certainly hope that my numerous meetings go well, that Essmart as a concept is well-received, and that I will receive useful feedback. So far, the social entrepreneurs I’ve talked to who are working in India have been most helpful, attempting to get me connected to anyone who is in the rural retail space. That these individuals would take a chance on a new idea and welcome me into their circle is most appreciated by the Essmart team, and I look forward to the day when I can do the same for aspiring social entrepreneurs.

I expect information overload from my experiences in the field, and I hope that I will be able to think critically (and quickly) about how these new learnings affect Essmart’s development. The enterprise is in its nascent stages; ideas are being coalesced as a type, and we are open to changes for the better. Right now is the most important time for us, and I know that I need to be all eyes and ears on the ground. Hopefully, I will be given the strength and alertness that is required. My schedule is tight, and I will get tired if I do not take care of myself. Oh, how I wish IAP were longer!

With that, I am signing off. This Emirates flight is most comfortable, and the lights have been turned off, revealing little lights in the ceiling that resemble tiny stars. Given that I need to catch up on my zzz’s, I believe that it is now time for me to begin dreaming about rural distribution and retail. When I touch down, well, I hope to make that dream into a reality.

And in the meantime, if you’re interested in Essmart, please check out our website and/or shoot me an email at diana[at]essmart-global.com. I would be delighted to hear from you!