(Summer ’15) Lily Bui, G

Lilian Bui (G, Comparative Media Studies)

Lily Bui will be working in Christchurch, New Zealand, in order to design, develop and deploy a mobile app for that tracks cyclist commutes, which will assess mobility patterns of cyclists after the 2011 earthquake. She will be working with the smart city trust SensingCity and the University of Canterbury.

CycleWaze: Finalizing Christchurch’s Cycling App Design

We have wireframes! In some meetings last week, Sensing City met with our app developers and signed off on the wireframes for our cycling app. This adds a nice note of finality to my fellowship as it wraps up this week. (Has it been three months already?) Much hard work has gone into user research, liaising with the cycling community (while being a part of it), getting funding for the project, presenting preliminary findings to city council, and much more to get us to this point. Now, the last — and hardest — part is to hand off the project to the rest of the team as I prepare for my move back to the States. There is still much more work to be done in terms of usability testing and data analysis once we have a working minimum viable product (MVP).

There is a term, “urban tissue,” which refers to recognizable patterns in the built environment — among buildings, streets, geographies. The metaphor connects the lived-in to the living, constructing the notion of the built environment itself as a living organism. Our research thus far sits at this nexus of the urban corpus, examining where infrastructure intersects with public and civic health as well as how digital technology might mediate and mitigate concerns in both worlds. Mechanisms for providing and receiving feedback are essential for assessing the “vital signs” of civic and public health, and what we have proposed in this paper is a research methodology that privileges feedback from relevant stakeholders at the community and city governance level to inform the design of digital technology. My hope is that at the end of the day, we’ve done something positive for the cycling community here and that the transportation data generated from the app contributes toward the rebuild of Christchurch.

This fellowship has, in many ways, given me a unique opportunity to engage with a real-world “smart cities” project, which is invaluable to my masters research. More than that, though, I’ve been able to connect with a place and a community that I would not otherwise had the opportunity to. Aside from “smart cities” stuff, I’ve learned something about resilience in cities that have been through natural disasters. I’ve had the chance to participate in a cultural revival around cycling and active transport in a city that has its historical roots in cycling. Because the University of Canterbury Geohealth Lab is a key partner in Sensing City’s cycling project, I’ve unexpectedly and happily forayed into human geography, a discipline I didn’t know much about before but now realize I have been a part of all along. Last but certainly not least, I’ve made friends, met people, and seen places that I want to hold onto for the rest of my life. So, although I won’t presume that I’ve made a lasting impact on Christchurch, but it certainly has made an impression on me changed me for the better.

At the Speed of a Bicycle: Changing the Culture of Cycling in Christchurch, New Zealand

I’ll start this post with a bit of news in the both the figurative and literal sense. Since the last update, I was commissioned by a local news outlet in Christchurch, New Zealand, called The Press to contribute an op-ed about the history of cycling in the city. The story ran on Saturday, July 25th in the Mainlander section of the newspaper, and it was also featured on the front page. (A digital version can be found here.) This was an exciting opportunity to synthesize some of the research that I had already been doing about cycling in the city. The interviews that I was able to feature in the op-ed gave voice to cycling advocates who are working to change the perception of cycling in the city and to make the roads safer for all those who use it. This is a cultural moment for Christchurch — one that will define what transportation looks like in the city’s future as it rebuilds, post-earthquake.

On the app development front, Sensing City has begun development of our app design in collaboration with a team called SpecialEyes. After a workshop held at Christchurch City Council and receiving match funding from the Canterbury Community Trust, we have moved forward into development and should have the app ready for testing by early September. Although this will be after my fellowship ends, one key thing I hope to do during the remainder of my time here is to create a road map for next steps, which I can pass onto the team members who will be taking over after I leave. The workshop that Sensing City held with Christchurch City Council helped me better understand the dynamics between citizens in the community and members in the council. The atmosphere is overall a collaborative one, and the city seems to be enthused by initiatives that benefit Christchurch and its residents.

Aside from working on the cycling project with Sensing City, I’ve also been participating in cycling events in Christchurch out of my own personal interests. I had the opportunity to help organize a GPS painting event with the cycling community here. GPS painting is an activity that involves using a GPS logger like Strava, MapMyRide, or similar mobile apps to map your route as you ride, walk, or move throughout spaces. Doing this, you can “paint” patterns or images using urban infrastructure. We were able to gather about 20 people to help paint a picture of the Arc de Triomphe in Christchurch’s streets to celebrate cycling as well as the end of the Tour de France. Since one of the local bike shops recently changed their location, we saw an opportunity to tie the GPS painting activity to the promotion of the move. At the end of our ride, we had a small picnic with treats and snacks at the new bike shop location.

Cycling in Christchurch is nothing new. It has rich history, and there is no shortage of advocacy groups that promote cycling in different ways here. The longer I spend here working on this project, the more I realize that there are limits to what technology (e.g. the development of our mobile app) can do to facilitate cycling in the city. Even if the infrastructure is improved and available (i.e. more cycleways), the growth of cycling in Christchurch, there is still more cultural work to be done to encourage more cycling overall. And this will be up to the community of cyclists in the city, which is already going strong. Change may not happen overnight, but it can at least take off at the speed of a bicycle.

Sensors, Cycling, Safety, and Cities

The CycleWays Project in Christchurch, Canterbury, New Zealand

Image: Christchurch City Libraries

In order to understand Christchurch, New Zealand, I’ve realized, one must first understand a little about catastrophe.

Don’t be mistaken. This is certainly no comment on the city’s current state. Rather, catastrophe, in the form of a natural disaster, formulates much of Christchurch’s recent history.

Shaken and stirred

Four years after a series of earthquakes destroyed Christchurch’s Central Business District (CBD), the city is still rebuilding. Pipes were broken, roads were fractured, buildings fell, cars crashed, and far too many people lost their lives. What I’ve learned after being here, though, through the stories that people tell and the moments that survivors remember, the earthquakes also surfaced immeasurable acts of human kindness. Clothes were donated, shelter was provided, and neighbors were rescued.

With an estimated 80% of its pre-quake buildings now demolished, the city is cast as a blank slate in this period of recovery, a palimpsest for architects, developers, engineers, urban planners and designers, artists, and citizens.

Importantly, there is a palpable tension between two competing value systems when it comes to the future of Christchurch: that of restoring the city to what it was before, against an equal and opposite desire to rebuild the city into something new.

Image: Lily Bui

The work of Dr. Susanna M. Hoffman, who researches the dynamics of disaster from both an anthropological and personal perspective, helps me think more deeply about what happened in Christchurch through The Angry Earth, a compendium of essays from disaster studies scholars:

“People’s recovery in the aftermath of disaster constitutes the Janus face of a major catastrophe, the social countenance laid over the physical reality. It can be a time of not just material but social devastation, fragmentation, and despair. For many, it can also be, quite remarkably, a time of social cohesion, purpose, and almost glory.”

Despite the relatively short amount of time I’ve spent here, I can confirm that the stories I have heard about the quakes fall along all parts of the spectrum.

Still, I find that my arrival has taken place at a good — even opportune — time, at the sweeping off of trauma, at a moment of readiness for resolve.

Cycleways, sensors, & safety

For now, I’ve set up camp in two places: SensingCity and the University of Canterbury Geohealth Laboratory. The former is a nonprofit organization that sits outside of government, industry, and academia and coordinates various projects to help stakeholders understand how data can form city management. The latter convenes researchers interested in Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in some form.

The problem before us is this: in post-quake Christchurch, though pre-existing modes of transport have been disrupted by diverted vehicle traffic and ubiquitous road works, cycling has endured as a convenient way to get around. It’s faster than public transport, free, and overall better for the environment.

However, cyclist safety and cycling infrastructure are other issues entirely. Christchurch is not a big city (population ~366,000 as of 2013), and its roads privilege cars, not bikes. Thus, motorists are not used to sharing the road, which is even harder to do with construction projects everywhere, and cyclists don’t have the proper mechanisms to interface safely with vehicle traffic. Sadly, there is precedent for cyclist injuries from cars, even one cyclist death. One solution is to improve the visibility, connectedness, and accessibility of cycleways (more colloquially referred to as ‘bike lanes’ in the States) in Christchurch.

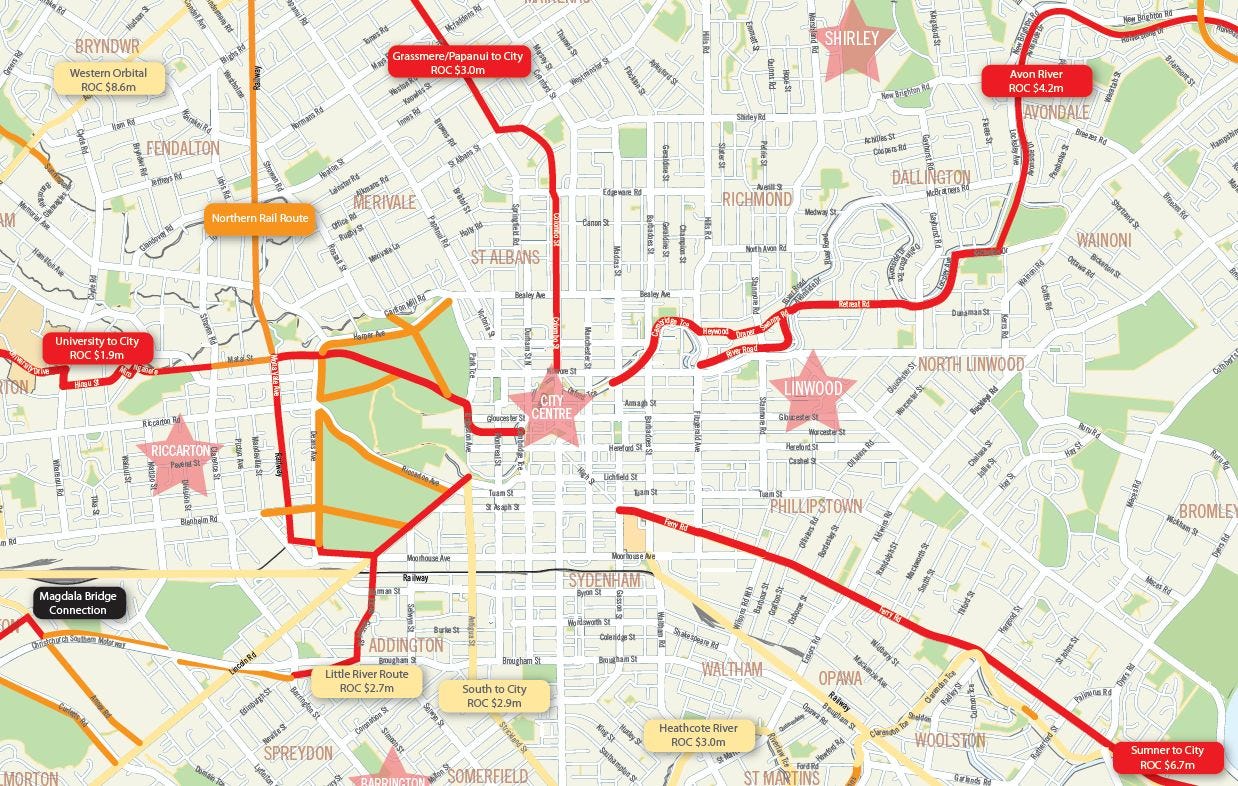

Extant cycleways were planned in top-down fashion, with city planners basing routes on where they believed cyclists travel most often. Lo and behold, this does not take into account where cyclists are actually traveling.

Image: Christchurch City Council proposed priority cyclways (Christchurch City Council, CCC)

Granted, this is largely because the city council has no baseline data to go off of, and much was built in a hurry after the earthquakes to get the city back up and running — form versus function.

Thus, what we’re trying to do with the CycleWays Project is to improve the availability of data regarding cycling routes, road-user behavior and cycling infrastructure in Christchurch. This involves designing a mobile app that collects GPS, timestamp, and other data about perceived safety levels of cyclists as they move through the city. Hopefully, by the end of the winter (yes, winter, and unfortunately so for this native northern hemispherer), we’ll have a working prototype app that (1) lets cyclists map their routes throughout the city and (2) collects some feedback about cyclist safety and cycling behavior in Christchurch.

Easier said than done, of course. Before development even takes place, I have my hands full with research about existing cycling app solutions, ethical concerns about data privacy (especially with GIS data), a bit of community organizing among cycling advocacy groups to better understand cycling culture and attitudes here, some user experience design and wireframing of the conceptual app, lining up media partners, and usability testing of the prototype.

Copenhagen and Amsterdam are, of course, often held as gold standards for cycling communities, but there is no such thing as a one-size-fits-all solution for cycling. Even Google, which recently released a Bike Vision Plan for Silicon Valley, takes into account specific, local constraints. Cities share some similar DNA, but the way in which that DNA expresses itself constitute myriad forms. For Christchurch, it must be about finding the right solution for Christchurch, not any other city.

Cacophony, community, and change

One key thing for me about working on a cycling app for a city is also being a cyclist in that city. I’ve inherited a mountain bike from a professor at Uni. As it’s my only mode of transportation other than walking or the bus (which is somewhat expensive and not convenient based on where I live and work), I’ve been cycling quite a bit. I’ve encountered, first-hand, many of the same frustrations that other cyclists report, chief among them: ambiguously drawn cycleways, little to no bike parking, cars and buses that swerve into cycling paths, and road works that present safety hazards in every which way.

Images: Construction makes it difficult to discern which paths to take in Christchurch’s CBD. (Lily Bui)

Not to mention, I’ve chosen to take on this project in the winter, during which the average temperature is around 3 degrees Celsius (~35 degrees Fahrenheit) and fewer cyclists are on the road in general.

Despite all this, I remain optimistic (whether by delusion or determination, only time will tell).

I’m optimistic because of things like the Winter Solstice Night Light Bike Ride, which I attended, and which happens every year and is independently organized by the cycling community in Christchurch. About four hundred people showed up in Hagley Park (Christchurch’s largest urban open space) with their cycles decorated with lights. Kids, parents, college students, young professionals, and seniors showed up with bicycle bells and whistles to ride around a pre-planned route in an illuminated caravan.

Images: Winter Solstice Light Bike Ride (Lily Bui)

Hagley Park has one of the few continuous shared-use paths in the city (wherein pedestrians and cyclists can safely travel) and its perimeters have the only cycle-only intersection signals in the city, making it an ideal place to host the event. A local science education center set up a kiosk and sold extra LED string lights to last-minute participants. Food trucks showed up at the end of the route to serve hungry cyclists. It didn’t matter that it was winter or that a biting southerly wind (from Antarctica, no less) had blown in. Events like this reinvigorate my enthusiasm for our work. They stand as a reminder that there is, foremost, a desire for safer transport, more accessible mobility, and (what I hope to be) positive change.

Coda

One final note. Hoffman reminds us that there is a place for equilibrium after disaster takes place, albeit temporary:

“…[A]mong the cacophony of place, event, and topic, a certain order generally emerges. For those suspended between havoc and wholeness, by and large a process ensues. Its steps are many and complex, yet they are almost as predictable as crawling, standing, and walking.”

And perhaps cycling too.

Making Christchurch a ‘Smart City’ in Post-Earthquake New Zealand

Image: SensingCity.org

I’m living in Christchurch, New Zealand this summer (well, technically winter in the southern hemisphere).

You might recognize the city’s name from international headlines a few years back when a series of earthquakes shook the city and destroyed much of its central business district. It was a tragic event that left 185 dead and much of the urban infrastructure damaged.

The reason that I’ve made the journey is to join the SensingCity Trust and the University of Canterbury’s GeoHealth Laboratory as a research fellow, a collaboration that formed as a part of the city’s reconstruction efforts.

Over $30 billion (NZD) will be spent on the city over a relatively short period of time. The vision is to allocate energy and funding toward various initiatives that equip the city with technologies that enable citizens to be more informed about the built and natural environment and to stimulate civic engagement throughout the process.

This is a keen match for my masters research at MIT Comparative Media Studies, which (for the time being) focuses on the design, communication, and use of air sensing data in cities and its potential impact urban design. I was also fortunate enough to be fully funded to travel, live, and work here by the MIT Public Service Center fellowship and the MIT International Science and Technology Initiatives (MISTI).

“The Sensing City Trust is a non-profit organisation working with Christchurch stakeholders to help them understand how data can inform decisions about city management. The Trust has two active projects — one focussed on the impact of air pollution on respiratory disease, and the other on cyclists generating data to inform cycleway development.”

I touched down in Christchurch on a windy Tuesday afternoon and was met by a welcome party of SensingCity colleagues. Because warm and cold ocean currents meet near the New Zealand islands, this causes conditions to be almost constantly windy. Turbulence is the status quo when landing in Christchurch, and I certainly learned this the hard way! Fortunately, I was met by a warm welcome party of co-workers at the airport, who were kind enough to help me transport my bags to my flat. My new flatmates are a blend of medical students and designers. We have an espresso machine, a WiiU, a piano, and AppleTV. I live within walking distance of Hagley Park (the largest park in the city), a handful of museums, and the beach. A professor of the University of Canterbury was kind enough to loan me a bike for my time here, so I’ll be able to get myself around more easily.

Image: Hagley Park’s botanical garden located next to the Canterbury Museum, Lily Bui

On my first day here, I spent time exploring the city. At the top of my list was the Christchurch Rebuild Tour, which focuses on the parts of the city most affected by the series of earthquakes. Over the course of 1.5 hours, I gained so much more context about how much construction and demolition have needed to occur — and are still in progress — years after the quake. It was also disheartening to hear more presently about the lives lost during the natural disaster.

Image: Ongoing construction in Christchurch, Lily Bui

This week, I set up shop in both of my offices (as I’ll be dividing my time between SensingCity’s space and the University of Canterbury) and held a handful of meetings with SensingCity team members and University of Canterbury Geohealth team members to better understand their goals for my project, which will focus on assessing cyclists’ perception of safety in existing cycleways.

Image: The EPIC building, which houses ~20 software companies in Christchurch. Also where SensingCity is located. Lily Bui.

Image: First day in the SensingCity office

Image: Crosswalk specifically for cyclists in Christchurch

After synthesizing the information during our meetings, I hit the ground running and developed a strategic plan/outline for the time that I will be here. Whether or not things go as planned is still meant to stand the test of time. However, putting our ideas down in one place was a good feeling:

SensingCity CycleWays Grandmaster Plan (view complete PDF)

This is the farthest I’ve ever moved away from home — in both space and time, given my crossing of the international date line. Yet, it’s the calmest and most ready I’ve felt while making the transition. Much of that is due to being surrounded by brilliant, supportive people both here and back home.

I’m looking forward to logging the progress of my work here, for those who are interested in following along. As always, I have arrived with my own assumptions and expectations in tow, but I have no doubt they will be challenged, matured, and revised along the way.

Cheers to this Kiwi adventure.