DUSP-PKG Fellowship: Allison Hannah Lee (G), Part III

Click to read Part I and Part II of Allison’s DUSP-PKG Fellowship experience.

I have been engaged with this particular project since March 2021, but during the past summer months as a DUSP-PKG Fellow, I have taken a far deeper dive into the community and the operational planning of this north central Massachusetts food system initiative. As the summer comes to a close, I am reflecting on the many takeaways from this experience, and some of the insights I’ve gleaned from working in a setting unfamiliar to me. As an urban planning graduate student (and an urban dweller all of my life), this work was framed by trying to understand differences in urban-rural America through the lens of planning and design. The seed of this framing was initiated by the spring 2021 Sloan USA Labs course, where my engagement with this project originated. Over the past months, this seed has grown into a passion and interest in this particular American divide. It has been cultivated by the lessons and experiences taken from this food project, and will continue in my work and studies going forward.

Below is one takeaway-in-progress related to how data informs the planning and implementation of projects in urban-vs-rural settings, as well as how that translates into how we might approach projects.

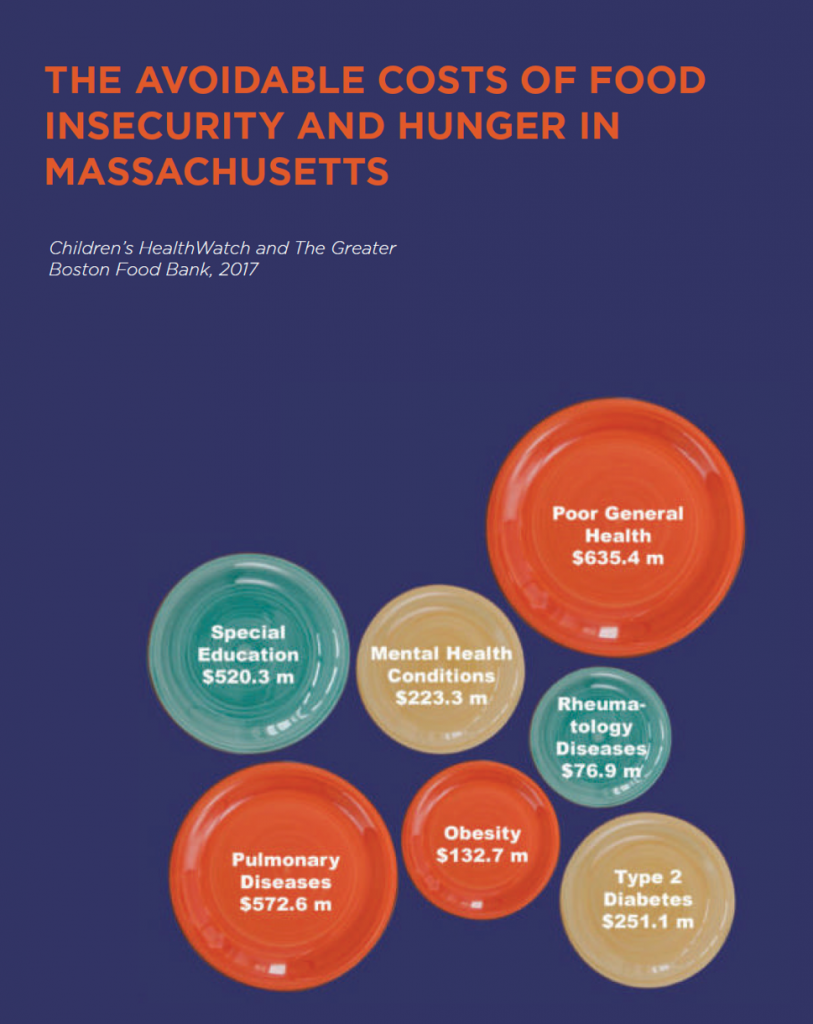

In the summer of 2019, just prior to the COVID-19 health crisis, the state of Massachusetts launched the ‘Food is Medicine’ State Plan. The plan set out to provide “a blueprint to building a health care system that truly recognizes the critical relationship between food and health and ensures access to the nutrition services our state residents need to prevent, manage, and treat diet-related illness.”[1] The state recognized that the prioritization of healthy food would not only improve public health outcomes, but also subsequent costs on healthcare deemed “avoidable”. Data from the Children’s HealthWatch and The Greater Boston Food Bank (2017) indicate that avoidable costs of food insecurity and hunger in MA include $251.1 million spent on type 2 diabetes, $572.6 million on pulmonary diseases, $223.3 million on mental health conditions, and $635.4 on poor general health.

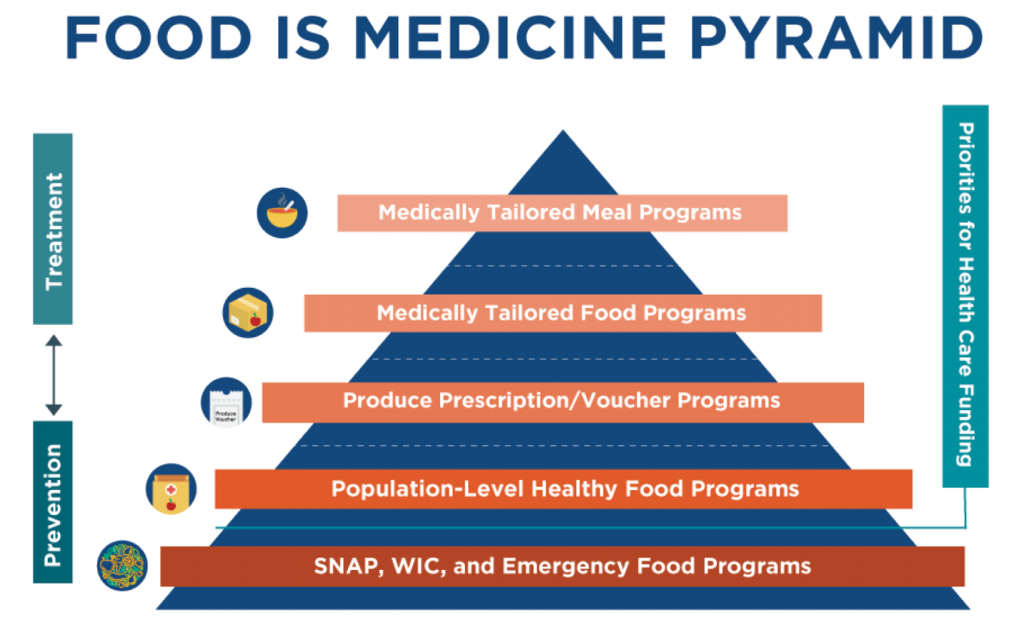

To address this, the plan outlined interventions, ranging from preventative to treatment-focused, and indicated where the state could boost their efforts. Specifically, it discussed four interventions:

- Medically tailored meal programs

- Medically tailored food programs

- Produce prescription/voucher programs

- Population-level healthy food programs

It did not include the fifth tier, “SNAP, WIC, and Emergency Food Programs”, viewing that as not a priority for health care funding.

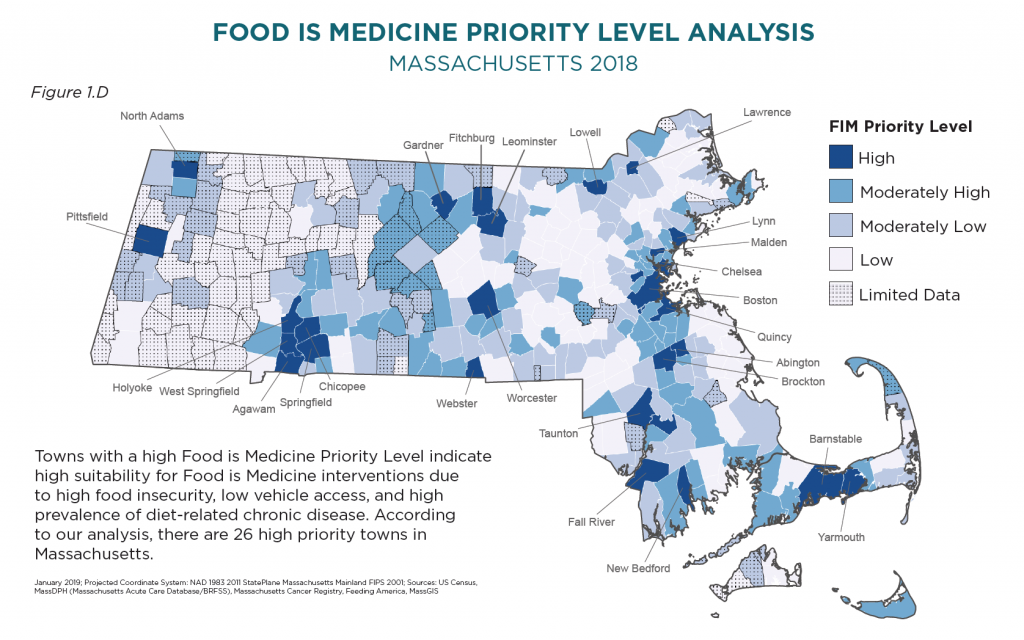

In order to most strategically propose the siting of programs, the plan calibrated greatest geographic need by looking at three main factors: (1) Food insecurity, (2) Vehicle access, and (3) Diet-related chronic disease burden. From this geographical analysis, 26 high priority towns were identified within Massachusetts state. Out of these 26 towns, 3 fall within our project footprint in north central MA (Fitchburg, Gardner, and Leominster).

While the spatial analysis provides insight into the geography of these contributing factors, it is important to note that data rarely tells the whole story. For one, the report notes limited data across great swathes of western and central MA. This missing data is linked to the third input factor: diet-related chronic disease burden. Additionally, as residents have mentioned on many occasions, maps don’t always portray what’s happening on the ground. For example, the siting of a farmers market in a town doesn’t necessarily mean it will serve residents facing food insecurities. Even with subsidy programs like SNAP/HIP, WIC, or farmers market vouchers, low-income residents have indicated hesitation or avoidance of such markets, for reasons such as price, feeling unwelcome, or inconvenient operating hours.

Data is massively helpful in understanding trends of health and population, and geospatial analysis paints a useful geographic picture. But in many cases, especially outside of major metro areas, datasets are far more porous and uneven. Often, they are too overarching (wide-reaching surveys gathered at the county level with zones of limited or no data) or they are too granular (personal interviews with small sample sizes and questions/answers relevant to that particular moment in time). This is a troubling reality for small NGOs based in rural places, who find themselves having to conduct repetitive interviews based on highly-specific needs, or working with inadequate broad stroke surveys. Most NGOs do not have the finances to obtain more adequate data from third party providers.

Another notable difference is in the application of data in the planning and implementation of projects. Large-scale urban projects, with ample funding and capacity, tend to operate more linearly, moving from feasibility, to planning, to all-in implementation. Modifications may be made over time for budgetary or management reasons, but inflexible timeframes usually mean that the majority of project members (consulting firms, design/planning groups, funding bodies) have wrapped up their portion and have left the project after implementation. For projects in a more rural and resource-limited environment, this linearity may not be ideal, or even possible. After feasibility studies and planning stages, an all-in implementation risks missing the mark or being unsustainable. This is not necessarily because the feasibility was incorrect or the planning was inadequate, but because there is a higher chance of unknowns, of limited data, or of moving targets. In these types of settings, incremental implementation (and iteration!) may be the key to the success of rural planning/design projects. Small steps also help to build trust within communities who have been let down so often in the past and who are weary to trust outside, or large-scale, projects.

This is a major different in approach between urban and rural settings, and requires very different sets of abilities and circumstances. For example, project leads and implementors in rural settings should be residents of those areas, not only because they understand the local context but also because the project may move at a pace significantly slower than urban projects. Iteration over time is highly important to sustain the rural project.

Momentum for change in rural settings ebbs and flows. Part of this is due to histories of failed promises made to rural communities, and the lost trust that ensues. Implementing new systems in rural communities takes another level of commitment and of engagement to ensure it is a system that works for them, and that they are willing to take ownership and carry it forward.

Allison Hannah Lee is a Master in City Planning candidate at MIT, focused on design and development. During summer 2021 she is partnering with the Community Foundation of North Central Massachusetts and local organization Growing Places to plan and implement a regional food hub that provides a better quality of life, of health, and of jobs in north central MA.

[1] Food is Medicine Massachusetts (FIMMA) (2019). https://foodismedicinema.org/

Interested in doing a Fellowship? Learn more about how to apply here!

Tags: Agriculture & Food, Climate Change, DUSP Fellowships, DUSP Fellowships 2021, PKG Fellowships