PKG Social Impact Internships: Ally Hong (’22)

Hey all! I’m Ally, a third-year undergrad returning from a gap semester.

Throughout my leave and quarantine, I have had the spacetime to reflect on my identity and purpose, which only involves a few existential crises… or seventeen.

It hasn’t been easy facing uncomfortable truths within my past. I learned that my first two years at MIT consisted of my attempts to grow branches without solid foundation in my roots. I got immediately obsessed with the sudden freedom, and I launched into the unfamiliar with nothing to fall back on.

As I indulged in making choices after choices that I wasn’t ready for, my indecisiveness worsened. I had no idea who I was and who I wanted to be. I neglected the self I used to know – most especially my cultural identity as a Korean American.

Such imbalance in identity was problematic early in my life. I was born and raised in Los Angeles, where I’ve been blessed to stay surrounded by a large Korean community; even my first language was Korean, which I naturally picked up at home.

I don’t remember when I first started attending pre-school, but my parents told me that during that time, I’d come home with my throat all bright red. No matter how many times they’d try to get me to open up, I wouldn’t speak a word. Their once talkative, bubbly child would come home sulky. After taking me to the doctor, they found out that I was so stressed in my inability to speak to my English-speaking classmates, to the point where it became painful to use my voice anywhere. As a result, they switched me into a Korean school.

This experience was one of many where I felt that my Korean-ness was a burden. Throughout middle school, I worked hard to lose my ridiculed accent as much as I could. As I began to sound more like a natural English speaker, I started to make fun of those who had a thick accent out of insecurity and pride. In my mind, doing so made me more like them. More accepted. More American.

I would code switch when I needed to, and I gradually transitioned from being “too Korean” for my friends to being “too American” for my family. The more visible I was outside of home, the more invisible I was inside. My Korean was terrible, and I stopped eating meals at the family table. During the few occasions that my parents would meet my friends, I’d crash as I couldn’t express myself fully to both groups simultaneously. My college acceptance, high school graduation, and birthday were all riddled with this confusion on how to act.

Once I moved to MIT, I forgot the little Korean I knew. I missed out on the fresh K-town meals and movie outings, and H-Mart was avoided as it was pricey and often out of the way. The connections that fostered my Korean-ness were nearly gone, with each visit to LA turning into an even fainter reminder of my past self. I constantly worked hard and played hard without proper meals, rest, and reflection. I wasn’t accustomed to eating alone this often. So separated. So isolated. Looking back, it’s funny how I got exactly what I had previously wanted. Soon enough, I burnt out and fell into heavy depression.

Then in March of 2020, the first ‘rona outbreaks in the US rolled around, and all of a sudden I was back at my parents’, attending Zoom classes. Everything was in chaos, and I could barely process anything. But I still felt more mentally stable with my mom’s welcoming meals, tea, and fruits (especially the ones that she’d bring whenever I’m working or studying). I re-centered my life on my faith and re-learned how to eat and sleep right. And although it was extremely frustrating having to stay inside for most of that spring and summer, reconnecting with my parents was such a blessing. I was slowly becoming more like myself.

Through conversation and K-dramas, I came to understand more about the world my ancestors lived in. My great-grandparents were born into the turmoil of Japanese colonization, and my grandparents lived during the chaos of the “Forgotten War”. My parents were born into post-war South Korea, reminiscent of the 1988 Seoul Olympics, rapid urbanization and industrialization, and censored media. Watching “Mister Sunshine”, “Ode to My Father”, and “Reply 1988” gave all their once-spoken stories extra dimension and shattered my biased perceptions of those who looked like me.

I realized I had inherited most of them from the world around me as a way to cope with insecurity and become more accepted. But what were their roots? I became curious about how these biases developed and where they originated.

Just in time, I was granted a PKG internship with Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders in Philanthropy (AAPIP) during IAP that would help me look at how media representation could contribute to shaping our biases.

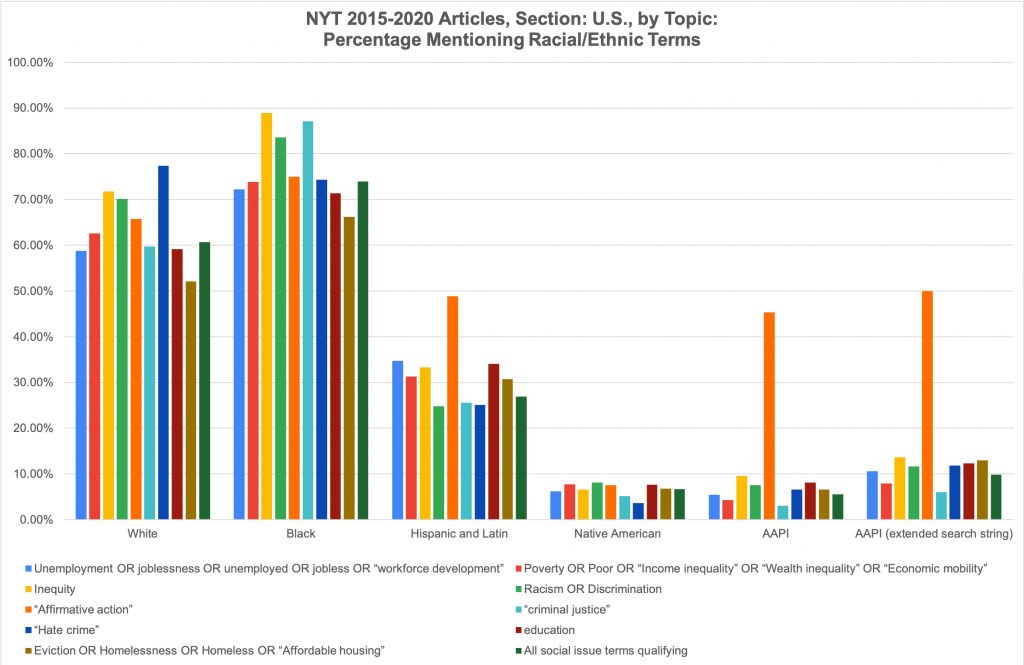

So far, I’ve been conducting research with Nancy, my supervisor (MIT ‘96), on how Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders (AAPI) are represented by various forms of media. I do so by analyzing news articles related to social issues, such as economic mobility, and how AAPIs are discussed relative to other races and ethnicities.

My first project utilized the New York Times’ Article Search API to collect the metadata and counts of articles mentioning various social issue terms and racial/ethnic groups.

Below is a chart that shows the percentage counts of all the US section NYT articles from 2016-2020 that have mentioned a racial/ethnic group.

The idea of equity in media is difficult to piece together, and I’m constantly asking myself what true fairness looks like. It’s not as simple as representing every community as often as those communities exist in numbers (for example, this method would result in mentioning white Americans in ~70% of all articles as there are ~70% white Americans).

Instead, fairness would involve further representing disadvantaged, marginalized communities accurately; furthermore, such portrayals have their own dangers of “invisibilizing” groups. In addition to these challenges, we only have limited resources, and the current state of our world often controls what is featured on the news.

Nonetheless, conducting research and closely observing how the media communicates are good ways to have a better idea of where to go from here; there are always ways to improve.

I’ve moved onto searching within databases to examine the language of other news sources, including the Washington Post, WSJ, LA Times, USA Today, NY Post, and the Chicago Tribune. I’m excited to uncover more as I continue my research with transcripts of news station outlets and older articles to analyze language towards these communities throughout our nation’s history.

All in all, I haven’t found all the answers to my initial questions yet, but I learned so much about better ways to answer these questions – specifically through proper implementation of social research and text mining through large databases, APIs, and websites!

It’s also been pretty helpful to re-familiarize myself with remote work and to gain insight amidst changing majors and transitioning back into school.

Here’s the first self-portrait I’ve created on Photoshop. In the background, the most relevant terms in 2019-2020 articles about AAPI peoples, from both the LA Times and NY Times, are displayed. These portrayals generally float around in my environment when people that look like me are described. Some are accurate, and some are not; in the end, the way they affected people’s perceptions had an impact on me when I didn’t know who I was. Although such labels are inevitably used in our world, we as people cannot be so easily simplified.

I’ve let go of the unrealistic expectations I’ve been building upon my entire life. I cannot become what people see me as, so I’ve made the conscious decision to step out in who I truly am, ever-changing, but no longer solely searching for the self in labels.

Now, I’m back to square one, but I already feel more whole than when I wasn’t.

Whether I dress in my hanbok (Korean traditional clothes) or my casual fit, I’m me. I’m not “too Korean” or “too American,” but I am a Korean American. I am Ally, a human soul, reborn in Christ and the life I have been blessed with.

P.S. Thanks for reading thus far! Feel free to reach out to me at allyhong@mit.edu if you want to learn more about any sources I’ve included and/or what I’ve been doing 😀

* which was around 50 words long as it included specific group terms, such as “Malaysian American” versus the umbrella term “Asian American”

Want to learn more about the PKG Social Impact Internships Program? Visit our webpage to learn about ELO opportunities for summer 2021, and stay tuned for information for fall 2021 postings!

Tags: Anti-Racism, Data & Research, Racial Justice, Social Impact Internships, Social Impact Internships IAP 2021